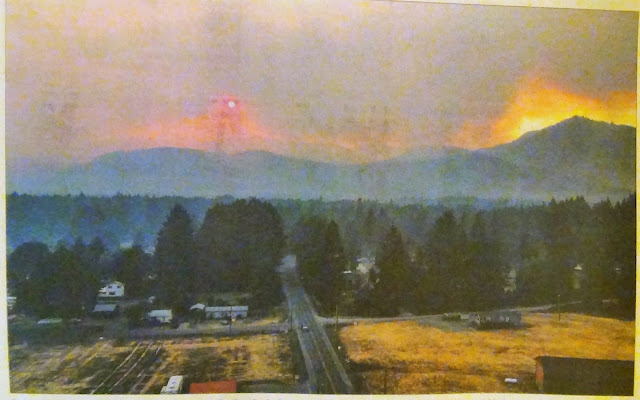

We could smell the woodsmoke over the aroma of our morning coffee. Outside, the rays of the early morning sun struggled to break through the hazy orange skies. Something wasn’t right.

We went down the hall to the breakfast room of our Yakima, Washington hotel. News anchors on the television there reported on forest fires in the nearby mountains. The roads were closed leading to Packwood, the next town we were traveling to. The town itself was being evacuated.

The front desk staff at our hotel looked bedraggled. They had been up all night booking rooms for those being evacuated as well as finding places to board their livestock and pets. They were also fielding calls to make room for off-shift firefighters battling the blaze which was bearing down on Packwood and the areas along the eastern border of Mt. Rainier National Park.

|

| News clippings of the Packwood - Goat Rocks fire. |

We had hoped to hike in that area of the park and use a hotel in Packwood as our base. We soon joined groups of other hotel customers in the same predicament to learn from each other what options were being considered to continue our respective travels. While we prayed for the people whose lives were being turned upside down in the nearby communities, we spent the rest of the morning dealing with cancellations, reviewing maps for alternate routes, and making new reservations, only this time for the western side of the park which wasn’t being affected by the fires.

It wouldn’t be the last time we would have to make adjustments to our plans during our travels. More fires, hazardous smoke, odd weather events, and other incidents would force us to alter our plans for a trip that was many months in the making.

Our plan was to travel for over 7,000 miles, minimizing as much as possible the use of the Interstate Highway System. After leaving the Midwest, we would cross the extreme northern part of the country along U.S. Route 2 to the Pacific Northwest, south down Highway 101 along the Oregon coast, then back east across the mountains and deserts on U.S. Route 50. Along the way, we hoped to see and learn more about this wonderful country we call home.

Part One – East to West

Our trip started one week earlier when we left our home in Illinois. It was not with more than a few hundred miles under our belts that I discovered that one of our car’s front tires was losing air at an alarming rate. In Fargo, North Dakota, the young man at the tire store there learned of our travels and scrambled his crews to get us patched up in short order resulting in a delay of only a couple of hours. It wasn’t until we were many miles north and west did we learn that the original woodchipper used in the movie Fargo was on display back in their museum.

“Ugh, I would have liked to seen that. Could have gone and took a look while the tire was being fixed,” I said disappointingly to Mary Kay.

“Hmm, yeah. What a pity,” she said sarcastically.

U.S. Route 2, The Great Northern Route

With the delays behind us, we finally approached Route 2 and began our journey on what is dubbed the “Great Northern Route.”

Soon, a car fast approached from the rear. The young people in the car weaved from right to left. Sometimes they would speed up and pass us. At other times they would slow down and we would pass them. Whenever we would pass each other, we would peer over and notice both the driver and the passenger were looking down at their phones, texting, Facebooking, or doing whatever young people these days do and find so important that the task of driving safely comes secondary. A couple of hours later, after they sped away and were many miles ahead, we saw them pulled over by a North Dakota State Trooper. We smiled as we passed them by. How satisfying.

Later, at a rest stop, an older Native American man warmly smiled at me while chatting away into his cellphone. He was using a language indiscernible to me. Perhaps it was one of the old tongues from one of the Lakota Sioux tribes in the area. Sadly, he may have been one of the few elders left who knew how to do so.

Nearby, we toured the museum at Fort Totten. The fort, now an historic site, was one of many that dotted the frontier during America’s westward expansion. They were established to keep the peace between settlers, railroad workers, and Native American tribes. The residence of the fort’s captain is now a very interesting B&B. Had we known of its existence, we would have made this one of our overnight stops.

Other towns had geographically and historically significant sites of interest. In Rugby, their claim to fame was that they were located at the geographical center of North America. In Minot, a replica of a wood stave church, common in medieval Norway and other parts of northwestern Europe, was erected in the town center in homage to the Scandinavian heritage of many who settled in this area.

In Montana, the open spaces and wide expanses of nothingness separated the sparsely populated towns. There was a certain beauty in the remoteness and starkness of our surroundings where views and observations otherwise mundane came into a focus in a more appreciative way.

Enormous farm combines, with their churning blades glinting in the sun, marched down the slopes of the gold-hued wheat fields side by side, like a battalion of tanks, kicking up dust from the chaff that floated over the road sometimes making visibility difficult. The fields were home to vast amounts of grasshoppers and other insects. They found refuge on the road, away from the harvest in the fields they once called home. Many met their demise as evidenced by their remains on our car’s grill and windshield. It reminded me of a saying comparing good days versus bad days: “Somedays you’re the windshield and other days you’re the bug.”

We confronted mile to mile and a half long trains on the tracks that paralleled the road, occasionally keeping pace with those that were heading in our direction. The loads were so large and so long that it sometimes took up to seven locomotives to haul the goods and cargo in the trailing boxcars.

Indian reservations were numerous. So too were their casinos. Some were fancy while others forlorn. An abandoned place of worship, with a name in a native language meaning “Pink Church”, sat high on a hill surrounded by an unkempt cemetery. Most of the plots had names typical of Native American culture and tradition, such as Sun Girl and George Long Knife.

Whimsical art and road side oddities were seen along the way. Some towns, like Glasgow, were proud of their middle of nowhere location and marketed themselves accordingly.

As we went further west, we watched our gas mileage plummet as we confronted strong 40 mile per hour headwinds that came down from the still far off mountain slopes to pummel and buffet the high plains. Big commercial rigs and mom and pop RV-ers were also pushing into these winds. Former smiles associated with their anticipated big and budget-friendly vacation have likely turned to fretful concerns and worry as they watch their gas tanks and wallets empty faster than a kegger at a college fraternity beer drinking party.

Glacier National Park

We overcame the winds and arrived at Glacier National Park via the Going to the Sun Road, an amazing road full of views and points of interest as it traverses and bisects the park. At Logan Pass, the parking area was packed with cars and people, even at the early morning hour when we arrived. Remote and isolated this was not.

We found a few parking spaces at a wide spot on the road a mile below. We walked along the shoulder back up to Logan Pass where the visitor’s center and various trailheads are located.

Signs suggest hikers carry bear spray due to the healthy population of grizzlies in the park. This was something I read about before the trip and dutifully purchased some from an online retailer. However, while almost every other hiker we saw carried an industrial-sized cannister and attached it to their backpack straps or belt loops, mine was of a very much smaller variety that fit inside the palm of my hand, more suitable to maybe deterring a determined Central Park mugger and not the menacing charge of an angry grizzly bear.

From the pass, we began our hike along the Highline Trail, a very popular, must-do trail if you are to day hike in this park. Along the first couple of miles, the trail parallels the Going to the Sun Road but does so along a precipitous ledge carved out of the sheer rock face of the wall that looms far above it.

At its narrowest, the Park Service has bolted into the rock wall a connecting series of chains which you hold onto while negotiating the narrow ledge. A slip here would lead to a gruesome death. Parts of your body would likely detach themselves from your pummeled torso as you bounced off of the rocks and crags protruding from the wall below. And then, in a final indignity, after you hit the road pavement hundreds of feet below, a passing car would run you over as a final good measure.

Commanding views of the Glacier Wall and other peaks and valleys came into focus as we made progress along the trail. Alarmingly though, what was left of the glaciers were small and growing smaller, receding rapidly up the valley. No wonder, for the temperatures have been in the mid-80s, way too high for this late summer/early fall date. The glaciers are simply no match for this kind of heat.

“What a shame,” a passing hiker commented looking at the same small glaciers we were looking at when we stopped for a trailside lunch at Haystack Butte Pass.

"I hear ya,” I replied back. “Perhaps they should consider renaming this park the ‘Not Too Many Glaciers Left National Park!’”

Numerous mule deer were seen both on and adjacent to the trial while on our way back to Logan Pass. We stopped to see several females and youngsters ahead of us. Nearby hikers called out saying that we should also look behind us. A male mule deer had apparently separated from the herd ahead of us and was looking to pass. Neither us nor he were alarmed at this confrontation. After a hesitating and cautious look, he scooted by with less than an arm’s length separating us and was soon back with his family.

More wildlife was seen when we later hiked up the Hidden Lake Trail. The first half of this trail was along a boardwalk that has been placed to deter people from wandering off and onto the adjacent fragile alpine tundra vegetation. The boardwalk eventually gave way to a gravel and rock path adjacent to various dwindling snow fields. On some of them, herds of up to a dozen or so bighorn sheep were laying down to keep cool from the unusual heat of our warming climate.

The next day, we embarked on a 14.5-mile round trip hike from the Jones Lake trailhead up to the Avalanche Creek trail which then led onwards to Avalanche Lake. Most of this hike was a long, contemplative walk through the deep and dark old growth cedar and hemlock forest. You could tell by the lack of wear on the trail’s tread that it is not walked by many others. But it should be since it is very quiet and serene.

In fact, we didn't see one other hiker for the many miles and two hours it took us before reaching the trail along Avalanche Creek where the popularity of the area grew due to many day hikers starting out from a nearby parking lot. The lake itself was disappointing. If you saw no other mountain lakes, you could say it was very pretty. But compared to the ones we have seen and hiked to, both here in Glacier and elsewhere throughout our travels, this one doesn't rate as well as the others.

Our final day in the park was spent at its northeastern corner. It is here that we received a whole new view and perspective of the park. Also, it is less visited and therefore less crowded. Our plan was to hike up to Iceberg Lake. However, due to heavy grizzly bear activity, the Park Service closed the trail to all users (even to those of us with both large and very tiny bear spray cannisters).

Instead, we hiked the south shore of Josephine Lake to Grinnell Lake about four miles distant. Portions of the trail veered off from the woods and followed the shoreline for a good distance. Views of the distant peaks, waterfalls, and permanent snowfields far above were spectacular and postcard-view worthy.

Eventually, the trail re-entered the bear infested forest for the remaining distance to Grinnell Lake. In fact, we saw a black bear browsing in the brush about fifty feet off of the trail.

We were greeted by a mini crowd of people once we arrived at the lake. A shuttle boat disgorged many of them who had motored in from a lodge in the area. Joining them were a newlywed couple (in tux and wedding dress) posing for their photographer with the mountains as their backdrop.

We walked down the shoreline a bit for some privacy to soak in the views of the amphitheater of mountains, snow, and waterfalls that nearly surrounded us. It was nice to sit and relax there after several days of hard hiking.

I noticed people moving along on the cliffside high up from the far shoreline. From our vantage point, they were tiny little dots of color among the grey walls of rock and stone. I used my binoculars to zoom in on them. Hikers were slowly climbing a trail that took them 2600 feet up to the perched glacier where one could touch the melt waters that fed the waterfall filling the lake we were now sitting next to.

I handed the binoculars to MK to take a look. “If instead of heading back to the car,’ I asked hopefully, “what would you think about continuing on and joining the others on that trail far above us?”

She was silent for a while as she scoped the far cliff-side. Handing the binoculars back to me, she said, "Fuck that."

And with that, our hiking in Glacier National Park had come to an end.

Back on U.S. Route 2

We pride ourselves on our efforts to travel on a shoestring. Doing so, we believe, allows for a more authentic travel experience. For example, we like to stay off of the tour buses and away from organized groups to make our own discoveries, shop in foreign grocery stores to make our own unique meals, and overnight in locally owned establishments to keep healthy the economy of the areas we are visiting. Doing all of this also allows us to stretch our dollars for use on yet more trips and journeys. However, traveling this way sometimes comes with unpleasant experiences and different kinds of costs.

Such was the case at our two-star Kalispell, Montana motel last night. The carpets were old, dirty, and threadbare. The scuffed cinder block walls (yes, cinder block) badly needed a paint job. The chairs in our room had numerous stains of dubious origins.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. We were woken up around midnight by another guest who had unlocked our door and entered our room. I bolted upright. “Who’s there!” I yelled. MK screamed. The unsuspecting lady who was mistakenly given a key to our room screamed as well. I don't know who was more frightened, her or us!! After checking to see if I soiled my shorts, we all went down the hallway to the front desk to sort out the mix-up and to make sure the lady was given a key to another room.

We tried to resume our much-needed sleep. But it came fitfully. Our mattress, which had to be one of the most uncomfortable ever, had a significant sag in the middle. It looked like the swayback of an old broken-down plow horse - and that is the way my back felt after sleeping on it!

We pulled away from the parking lot the next morning fuzzy and sleepy-eyed. “You sure know how to pick ‘em,” MK said wearily as she looked back at our jail cell-like motel, now receding in our rearview mirror.

We continued our Route 2 journey with a mid-morning stop in the mountain town of Libby, Montana. This small community was once ground zero of one of the worst man-made environmental disasters in American history.

It occurred over a period of many decades when the population was essentially poisoned by asbestos dust that had continually and consistently blown in from the area’s vermiculite mines. It has only been a couple of years since the EPA has declared the area “clean.” While hundreds have died, it is estimated that currently one out of every ten residents have an asbestos-related disease.

What does a town with such a dark history do to make it livable and more tourist friendly? “I know,” a chamber of commerce official had probably once said. “Let’s host an annual Chainsaw Carving Contest!!”

We happened to be passing through at the right time for men and women from all over the world had descended on this tiny village to compete against each other by carving and sculpting out of a raw, unfinished logs a statue or an image, usually of a wildlife figure or scene.

Most of the competitors travel the country, from contest to contest (apparently other chambers of commerce have had similar thoughts), and earn their living from potential prize money (the purse at this particular contest was a paltry $15,000) and by selling their work (we bought a small pumpkin carved from wood to add to our Halloween collection). "I am a wandering gypsy chainsaw artist,” one carver who called himself Thor, told us. “I don’t know if I make a living, but I do have a life.”

Down the road, we stopped at Kootenai Falls for a picnic lunch. Fly fishermen with gear in tow preceded us down a nearby trail. While they descended to water’s edge, we walked up and over the self-proclaimed Swinging Suspension Bridge (it lives up to its name, trust me!) that spans the river far above the rapids, falls, and cataracts.

From there, Route 2 entered into Idaho for a short journey across that state’s panhandle. At Bonner's Ferry, we reached the most northern part of our trip. There, we could see the nearby wildfires that were clearly visible on the slopes of the mountains that loomed over the town.

In Sandpoint, the downtown’s tourist-friendly shops catered to those out for an afternoon stroll. But not too friendly, mind you. After a daily dose of ungodly morning swill from our motels’ breakfast rooms, we were on an early afternoon hunt for a proper cuppa. But to our dismay, all of the coffee and pastry shops had already closed for the day.

We finished our last miles on Route 2, our old friend, while traveling through central Washington state. Scavenger birds, raven-like by their appearance, flittered and then flew off from their feast of a dead roadkill carcass as we approached them at high speeds.

Wheat field after wheat field stretched as far as the eye could see, much like what we experienced in west central Montana days earlier. Interestingly, the farmers in these here parts plow and plant their wheat right up to the edge of the road pavement. There are no road shoulders nor sizable rights of way in which there are fifty or so feet of ditches, grass, and then a fence before the plowed and planted field begins. Nope, not here. Wheat right up to the edge of pavement.

We left Route 2 for good when we detoured north toward Grand Coulee Dam, sometimes referred to as “the eighth wonder of the world,” The Columbia River waters it holds back are used to irrigate nearly 700,000 acres (do you like Washington State apples? Then thank Grand Coulee Dam). Its turbines generate enough electricity to power 2 million households throughout eight of our western states. It is said that the concrete used in its construction could create a 4-foot-wide sidewalk, 4-inches deep that would wrap around the world twice. It’s a marvel at what man can accomplish, isn’t it?

Man-made marvels changed to those nature made as we continued our remaining westward travels through the downstream Columbia River valley. Magnificent canyons and ravines (what they call “coulees” here) have created unique landforms and geologic areas of interest.

Much of what we drove through was created at the end of the last ice age when an ice dam formed in front of a massive glacier holding back its melt water. The dam gave way sending an enormous cascade of water miles wide and hundreds of feet deep speeding along at 65 miles per hour to create what we saw and traveled through today. My God! Can you imagine such a cataclysmic event?

Part Two – North to South

Our walk was along a tiny, and I mean very tiny, five-mile portion of this epic trail. We chatted briefly with several thru-hikers, those that were hiking the entire route. One young man started his journey at the Mexico border back in early March. “It’s been quite the trip,” he told us, looking fit and trim. “And I’m on schedule. I’ll get to the Canada border by early October.”

Soon after we congratulated him on his accomplishment and bidding him continued good luck, we chatted with two other thru-hikers, both from England. “We’re loving our American adventure,” they said. “It’s been slow going, but we’re confident we’ll finish before the snows come.” There were some other day-hikers we briefly talked to, but no more thru-hikers. We were hoping to run into Reese Witherspoon but no such luck (for those that just got that joke, please raise your hands!).

We were fortunate to find a last minute and suitable alternative accommodation for the next several days when we later arrived in the town of Chehalis. This would serve as our base from which we would explore the western portions of the national park.

Mt. Rainier National Park

Mt. Rainier was brutish and muscular in an in-your-face kind of way. It just overpowered the scene in front of us. The views of grey rock and stone, covered here and there by enormous snowfields, dominated our views. Waterfalls and glaciers, heard cracking and groaning off in the far distance, descended from its flanks. Its heights, brilliant white with snow, came in and out of view as the clouds moved about.

We were on the Park’s signature trail, the six-mile Skyline Loop Trail, that took us from the Paradise lodge and parking area up and adjacent to this magnificent mountain. The entire trail was above the tree line and surrounded by alpine tundra which afforded unobstructed views.

This specific route and its side trips were recommended by Sandy, a very helpful and friendly volunteer ranger with the park service. His missing arm didn’t seem to deter him from regularly hiking the park’s trails and paths, some of which he was recommending we do in the coming days.

When on the trail later, a fellow volunteer was stopping all of us hikers, asking where we were from, what trails we planned on hiking, and then gave various tips and ideas on how to get the most out of our time here at Mt. Rainier.

We took him up on some of his ideas early in the morning on the following day when we headed up a three-mile path in the mist and fog to Snow Lake, a pretty little alpine lake sitting in a cloud enshrouded bowl surrounded by mountain sides and cliffs. We then took the three-mile loop around Reflection Lakes stuffing ourselves with trailside blueberries while waiting for the clouds to lift and for Rainier to show itself.

At least we thought they were blueberries for they certainly looked like them. They were growing wild everywhere along the trail. We were uncertain as to their edibility until we saw other hikers eating them by the fistful. That was enough to convince us that we too should indulge. And indulge we did. While they were delicious, they didn’t actually taste like a blueberry. But no one else was keeling over so we thought all was good.

Soon, another couple came around the bend in the trail and saw us munching away.

“Are these safe to eat?” they questioned as they began to cautiously nibble on the berries.

“We’ve seen many other hikers gorging on them so, yeah, we’re pretty sure,” I said between bites. “If not, we can discuss further when we meet you later at the E.R. when they pump our stomachs!”

They laughed nervously. “Maybe we can share a room!”

The delays caused by this fun and frivolity brought us to a late afternoon hour when the clearing clouds began to part themselves. Rainier took advantage and showed itself in all of its glory. The views were impressive both at Reflection Lakes and then later when we went on our last hike to view the Nisqually glacier, one of many Rainier glaciers with water falls and milky white water in braided, fast-moving rivers far below.

South Towards Oregon

We looked forward to visiting Mt. St. Helens to witness what the destruction of a devastating volcanic eruption of 40 plus years ago can do to the natural landscape. As we drove up the park road though, our mood darkened for the morning’s cloud deck had descended down to the levels where viewpoints were plentiful.

We watched a very informative twenty-minute movie at the Johnson's Observatory visitor’s center about the Mt. St. Helens 1980 eruption and the science and ecology learned from it. In dramatic fashion, after the movie ended, the screen and curtain behind it rose slowly to reveal an enormous picture window through which you could now see...wait for it....drumroll please.....NOTHING!

We were supposed to see the real thing: Mt. St. Helens in all its glory and grandeur. Instead, all we saw was a blank slate of grey clouds, fog, and spitting rains. We did however enjoy the various exhibits and first-hand accounts of those that survived the blast. They were miraculous and sobering all at the same time.

We arrived about 90 minutes later in the town of Longview. We met up with Dave and Paul, fellow travelers who we first met ten years ago. We were all sent to Ukraine as part of a U.S. State Department delegation to help teach democratic principles and local government best practices and procedures.

It was great seeing them again, catching up, and reminiscing about our past shared experiences a decade ago. We also lamented the on-going crisis there in a country we have collectively grown to love. We keep in touch with our friends back there and updated each other on how they and their families are doing the best they can with the unimaginably bad and very unnecessary situation of Russia’s making.

When our waiter took our group photo, he asked how we knew each other. Because we stumbled and hem and hawed as we tried to give him the background and details of our relationship he said, “Sounds weird. Were you CIA or something?”

After parting ways, our drive took us into Oregon, our 49th state. We smiled at each other when we crossed the Columbia River since as of now, we only have one state left to go (Hawaii), and we will have visited all 50 of our great United States.

We smiled again when at the gas station, we learned that there is no such thing as self-serve here. There are attendants that fill your tank for you. And, when I went inside to buy some goodies and gave the clerk a ten-dollar bill for a four-dollar charge, I got a full six dollars back, not a fiver and fistful of change. Seeing my puzzled look, the clerk said, “There’s no sales tax here in the State of Oregon.”

Highway 101 and the Oregon Coast

But man! This sure is a scenic and beautiful part of the country!

At Cannon Beach, we walked the sandy beach and shoreline toward Haystack Rocks, a picture-worthy volcanic plug of basalt right off-shore that dominates the coastline view, now the home of gulls and puffins. We were there at low tide allowing us to walk right up to the rock. Volunteer naturalists walked amongst the gathered masses to describe to those of us willing to listen their explanation on the ecology and geology of the Rocks. They were also quick to warn us not to step onto the exposed barnacles and other sea creatures now clearly visible and exposed due to the low tide.

Numerous Lewis and Clark sites historical sites exist here and in areas near the mouth of the Columbia River. This area marked the final destination of their 1804 Voyage of Discovery journey in the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase to see if a water route existed from the east to the Pacific Ocean. There wasn't, of course, but they did reach the Pacific Ocean via various rivers and mountain passes and landed here near the mouth of the Columbia River. "Ocian (sic) in view! O! The joy!" Meriwether Lewis wrote in his journal.

We stopped for a proper cuppa and a scone before sleepily and groggily making our way further south the next morning. You see, at 3 a.m. last night, the couple in the room above us began a marathon session of spirited and very energetic nocturnal activities. You could hear everything, and I mean EVERYTHING!!!, if you catch my drift. And the guy? We had to give him kudos since his endurance was most impressive. But after a while, enough was enough.

“Holy Jesus!” Mary Kay exclaimed after what seemed forever, squeezing the pillow around her ears. “Enough already! That poor woman!”

“Yeah, no kidding,” I said in false agreement. Truth be told, I harbored a secret. I had become envious of the guy and his staying power.

Down the road, we stopped at the Tillamook Creamery and walked along their viewing decks from which you could view the cheese making process. There were free samples, interesting self-guided tours, cheddar cheese this, and cheddar cheese that. Here, it was cheese galore!

Nearby began long stretches and grand vistas of the ocean, rocky cliffs, crashing waves, and distant and largely empty sand beaches. Whales breached the ocean’s surface spouting and exposing their massive tail fins right offshore. Historic harbor towns sheltered colorful fishing boats, bobbing in the gentle swells, waiting for their toil the following day. On the piers they were tied up to were lounging sea lions, their bellowing distinctive call heard from blocks away.

Near dusk, we slurped bowls of clam chowder at the world (at least in the part of the world) famous Mo's restaurant. In the dying light of the day, the silhouettes of historic lighthouses served to back-drop our casual stroll through oceanside neighborhoods and quaint commercial districts on the way back to our motel. Once there, we hit the feathers. Unlike last night, we hoped for a well-earned and, hopefully, full night of uninterrupted sleep.

At Cape Perpetua the following morning, we visited places with names like Devil's Churn, Spouting Horn, and Thor's Well. Unfortunately, we were there at low tide. At high tide, one can only imagine the crashing waves that would occur in such places. Regardless, we walked along the rocky shoreline amongst the features with these names and marveled at the rock and wave patterns throughout.

We walked away from the shoreline and into the forest. The area's largest Sitka spruce tree was found on a poplar two-mile round-trip trail leading from the visitor's center. The 550-year-old tree is 225 foot tall and 15 feet thick. We were amazed at the thought that a seedling, sprouting from an otherwise unassuming pine cone, emerged from the soil before Christopher Columbus left on his first of many voyages to the Americas.

Herds of elk were seen near one of the trailheads. The lone male in the group kept nosing the females urging them to get up and move along to other fields where there was better grazing.

A wooden stave aqueduct near another trailhead, used to transmit fresh water to far-away places, was in serious need of repair for it had numerous leaks spraying water out onto the adjacent road. Given that our car was filthy from three weeks of driving across the country, we took advantage and used the leaks as you would a touchless car wash back home.

Lava Beds National Monument

We learned last night while in Klamath Falls, Oregon that the Lake Tahoe area of northern California, our planned destination for later in our journey, was choked with forest fire smoke due to the growing and not yet contained Mosquito Creek fire.

Air conditions were so bad that the area earned an air quality rating of “Hazardous”, the worst of the worst. So, with a fire bearing down on the town and the air we’d breath likely carcinogenic, we scrambled all evening in our hotel room to research alternative destinations and make the appropriate plans and reservations to bypass the worst of these fires.

Our alternative route took us through Lava Beds National Monument at the Oregon/California border. Our seven-mile hike there was through a landscape full of desert scrub interspersed with dark black rock. Over a period of hundreds of thousands of years, numerous volcanic eruptions layered the land with lava flows. In many areas, the edges of the flowing lava cooled faster than the still molten and moving lava within and, like a straw laid on its side, left behind hollow, hard-edged tube-like caves. In some of these, the ceilings have collapsed allowing us to access their depths. In one of the deepest, an ancient ice lake had formed and remains to this day. We prayed that our flashlight batteries wouldn’t give out since we’d never find our way back in the resulting absolute darkness.

Over time, soils had formed in other areas were the lava flows cooled. Wind-blown and bird deposited seeds took hold. Desert scrubs and grasses began to thrive. Junipers trees sprouted and dotted this evolving landscape. Unfortunately, the junipers, some over 500 years old, were eliminated in an instant when a lightning storm last year struck the area causing widespread fires and destruction over what was a pristine wilderness environment. The ash that still remains billowed from our footsteps as we moved about but was soon carried away by the winds.

We left to beat the oncoming storms. Unobstructed by the far-off views, we could see veils of rain hanging from the growing and menacing clouds soaking the areas we had been hiking through only a couple of hours before.

Mt. Shasta

The rains we saw yesterday turned to snow at the higher elevations. So much so that in Lassen Volcanic National Park, one of our alternative destinations due to the issues in Tahoe, they had closed the central portions of the park road due to an early season accumulation of snow. So short-cutting our route through the park to visit its natural wonders was out of the question.

Once again, conditions required us to change plans so we detoured over to the Mt. Shasta area. Before arriving, the road took us through the small town of Weed. Forest fires earlier in the year caused mass evacuations here. While most of the town was spared, several blocks were burned to the ground. I cannot imagine the stress of living with a fire bearing down on you, not knowing if your home and your block are in its path or if Providence will intervene and spare you from the fate that many of your neighbors had to confront.

At the town of Mt. Shasta, we walked along a wonderful seven-mile loop trail that encircled Siskiyou Lake. The trail veered in and out of the forest and then edged along the lake’s shoreline. From there, we found ourselves in awe with views of snow-covered Mt. Shasta in the background.

The lush and wet environment soon changed to something more desert-like as we later headed toward the end of the north-to-south portion of our trip. Drought conditions are such that water reservoirs are seriously depleted. The "bathtub ring" effect was very evident, particularly at the Shasta Lake reservoir. This is alarming in that the waters from this reservoir serve to irrigate the agricultural fields of the San Joaquin Valley where many of the fruits and vegetables we enjoy back home are grown.

Part Three – West to East

A "check-in" sign was haphazardly nailed on the wall above the door of the adjacent liquor store. After I discovered the door to be locked and the store dark and empty, I noticed, almost by accident, a tiny post-it note off to the side saying I should go next door and check-in at the café.

The door squeaked menacingly when I entered. The place was empty except for one lone older gentleman. The tattered cowboy hat he was wearing was stained with grease and grime. He was sitting by himself at a back table drinking a brown-colored liquor (neat, no ice) from a small glass, the only thing on the table. He simply stared at me while taking long slow sips from his glass as I walked around looking for someone to check me in.

"Want sumptin' to eat?" he finally asked me as I peered around one corner then another looking for some help.

"No. But I do want to check into our motel room."

Without saying a word, he took another deep sip and slowly slid his chair back from the table, its legs scratching and screeching on the wooden floor. He walked away and disappeared back into the kitchen.

After a moment or so, he peered back around the corner with a look that suggested I should have known to follow him. He motioned with his fingers to meet him in the back room.

"Need your credit card," he said with no emotion or urgency. "And sign here." He handed me a registration form and I dutifully did what I was told.

"Park in front of the gift store and walk up the sidewalk to find your room," he said as he handed me the key and the receipt for my credit card.

Paint had peeled away from the walls of the adjacent building. Vines and creepers climbed up the walls pulling away some of the siding. Through it all, I could make out the words: "Gift and Ski Shop." All the lights were off. The windows were soiled with dust and dirt. The place was dark and dank. Peering in, it seems the place hasn't sold a gift or a ski in decades.

Our route took us through this devastation toward the southern entrance of Lassen Volcano National Park where, upon entering, we could see the evidence of vast fires that have destroyed this area as well. The road through the central portions of the park was still closed due to early season snows (which required us to detour around it yesterday), but by entering past the southern gate, we can now check off another national park on our list of parks and monuments we have visited throughout the U.S.

After the performing the mundane tasks of shopping for groceries and doing our laundry in the town of Susanville, we crossed into Nevada to spend the night in Reno.

“You weren’t paying attention! What’s wrong with you?” MK was not happy.

“I was paying attention, just didn’t see the deep sand – it blended in with everything.”

‘I’m getting out to push. Jam it into reverse when I say go!”

“Let me push. I’m the one that got us stuck.”

“I said I got it!”

Some grunting and a lot of swearing soon commenced.

“Ok, you push.”

“Like I said,” as I got out of the car, brushing past MK as she got behind the wheel.

We finally broke loose from the sand’s grip and got back out onto the road. This was followed by one of us trying to be cheerful while the other commenced a long period of seething silence.

All was well by the time we stopped at various petroglyphs and rock art sites. One in particular was at the Grimes Point Archaeological Area where the Tai Ticutta (Cattail Eaters) peoples, now the Paiute-Shoshone tribes, lived 2,000 to 3,000 years ago adjacent to what was at one time a vast lake. At the Hickison site, ancient peoples from even longer ago (10,000 years ago, in fact) also left behind their rock art. The meanings behind of their images continue to puzzle archaeologists.

Roadside markers detailed the area’s more recent history. The road was part of the Lincoln Highway system, the first transcontinental road in the United States. It was built within the corridor that was once used by the Pony Express. Riders traveled for 75 to 100 miles a day past remote stations and outposts where they would change horses every 10 to 15 miles. Operational for only 18 months in 1860-61, the Pony Express went out of business with the invention and widespread use of the telegraph. Not much is left of this famous part of American history other than signs indicating where the trail paralleled or crossed the road.

Between Austin and Eureka there was nothing but austere and desolate windblown desert lands along a road that is flat and straight as an arrow. While a book about the road aptly describes it as "70 miles of Great Basin nothingness,” I would suggest my alternative description is equally fitting: “You lose it our here and you're in a world of hurt”

From there, the rocky scree-filled trail took us up to 11,000 feet. There, in a cirque at the head of a valley encircled by imposing vertical walls of rock and stone, are some small snowfields that still exist in an area once known for its mammoth glaciers. While glaciers as we know them are all now long gone, the evidence they left behind is seen everywhere. The trail traversed the terminal and lateral moraines, made up of loose boulder, rock and gravel that the glaciers left behind before their inevitable extinction.

However, rock glaciers, a geological term I hadn’t heard of before coming here, do indeed exist. On the edges of the rock filled cirque through which we hiked were fields of ice, but they were hidden under the rock scree that had sloughed off of the slopes and permeated the otherwise exposed ice. These rock glaciers move just like a regular glacier except you can’t see the more typical white and grey ice fields. I spoke with a park ranger who said that he too had never heard the term “rock glacier” until he was posted here at Great Basin. “It is a geological oddity seen nowhere else in the park system, as far as I know,” he said when I quizzed him about them at the visitor’s center.

The next day’s trail climbed gently at first through groves of golden yellow birch and aspen. They had begun to turn early in these first few days of fall due to being located at these high mountain elevations. From there, the trail led through open meadows with expansive views of the mountain ranges and the flat, brown desert wasteland down and far below.

We eventually arrived at a 10,800-foot saddle were two route choices presented themselves. Wheeler Peak, at 13,100 feet, rose above us to our left. The trail to its summit was defined and maintained by the park service. To ascend its heights would require negotiating an endless series of steep switchbacks and a knife-edged ridge when nearing the top.

Bald Mountain, at 11,500 feet, rose above us to our right. The route was a cross-country one with no defined trail that ascended over endless fields of suitcase- and bowling ball-sized rocks and scree. Despite the rocks, this route seemed to be more senior citizen friendly, so the choice was made.

What little trees remaining at these elevations served to hide several deer that roamed these heights. They peered through the branches at us as if they were either curious as to what we were doing here (I later learned that only one to two other hikers take this route on any given week) or puzzled to see us and our foolishness.

Soon, the trees gave way to a few remaining sporadic krummholz trees, stunted and severely slanted away from the onslaught of big blows from relentless winter storms. All that was left before us was more rock and scree upon which we gingerly stepped, twisting and torquing our joints, all the while gasping for what remained of air at this high elevation.

We eventually and successfully reached the summit with sore bodies, jellied ankles, and thoughts of scheduling knee replacement surgeries when we return home. But our spirits were soaring for this challenging trail was the last of the longer hikes we would be taking on what at this point had been a five-week cross-country adventure.

Back to Route 50

We continued our eastward progress on U.S. Route 50 and soon entered Utah. The road traversed much of the sameness and nothingness we found while traveling the road through Nevada. Between the border and the next town was a straight, unrelenting 90 miles without any break - no services, no pull-offs, no rest areas…nothing, absolutely nothing.

Eventually, we drove adjacent to a vast dry lake shimmering white from the salted crust of what was once its underwater lake bed, placed there by Mother Nature herself to break up the monotony. It now exposes its brilliance to passers-by, blinding them as the rising sun reflects off of its sheen and into our eyes. Signs warn the curious not drive or walk out onto this whiteness for while it appears dry, it is in fact a firm yet brittle crust covering the mud, muck, and salted mire underneath, sure to get you or your vehicle irretrievably stuck.

Filling our car’s windows beyond the lake were views, both far and near, of buttes, mesas, spires, canyons, and arroyos. I recalled my college days when one of my favorite topics was geomorphology - the study of landforms and the physical features of the earth’s surface - forgetting more of the terms than I can now recollect.

Journey’s End

Route 50, our companion - the “Loneliest Road” – got absorbed by Interstate 70 when we reached the center of Utah. Our thousands of miles on back roads, U.S. routes, State routes - anything to avoid traveling on an Interstate Highway - had come to an end. From here on out, the four lane soulless Interstates would be our means of travel.

When we entered Colorado, we took a side trip through the Colorado National Monument near Grand Junction, a very underrated gem of the nation’s parks and open space system. The red rock landforms reflected pleasingly, contrasting sharply with the dull browns and greys of the expansive flats of the past several days.

Leaving here marked the end our adventures, the types of which we experienced over the past many weeks. The rest of our days on the road in Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, and our home state of Illinois were to be spent visiting and fulfilling obligations to a vast array of family and friends. For some, we would help them on their own journey along their life’s new path. For others, sadly, we would say goodbye for their life’s journey has come to an end.

We have traveled over 7,000 miles through 14 states and 8 national parks and monuments. We have hiked over 125 miles on trails from the easy to the perilous through, over, and by endless deserts, towering mountains, imposing glaciers, alpine lakes, verdant rain forests, remote beaches, mighty rivers, and placid streams.

At the outset, we hoped we would learn more about America, the country we call home. And we did so beyond all expectations. Along the way we have driven through fields of corn, soybeans, and wheat extending to the far horizons. Ocean waves, rocky shorelines, ancient trees, and wildlife of all descriptions have filled our camera’s viewfinders. We have found comfort and hospitality in big cities and metropolises as well as in small towns and villages. We have been saddened at the smoke-filled skies, numerous wildfires, and the evacuated and, sometimes, burned out towns. And we have marveled at the diverse people we have met and the pieces of our nation’s rich history, its varied culture, and its wide-open spaces which existed at every turn.

Man! What a wonderful country we live in!

“Ugh, I would have liked to seen that. Could have gone and took a look while the tire was being fixed,” I said disappointingly to Mary Kay.

“Hmm, yeah. What a pity,” she said sarcastically.

U.S. Route 2, The Great Northern Route

With the delays behind us, we finally approached Route 2 and began our journey on what is dubbed the “Great Northern Route.”

Soon, a car fast approached from the rear. The young people in the car weaved from right to left. Sometimes they would speed up and pass us. At other times they would slow down and we would pass them. Whenever we would pass each other, we would peer over and notice both the driver and the passenger were looking down at their phones, texting, Facebooking, or doing whatever young people these days do and find so important that the task of driving safely comes secondary. A couple of hours later, after they sped away and were many miles ahead, we saw them pulled over by a North Dakota State Trooper. We smiled as we passed them by. How satisfying.

Later, at a rest stop, an older Native American man warmly smiled at me while chatting away into his cellphone. He was using a language indiscernible to me. Perhaps it was one of the old tongues from one of the Lakota Sioux tribes in the area. Sadly, he may have been one of the few elders left who knew how to do so.

Nearby, we toured the museum at Fort Totten. The fort, now an historic site, was one of many that dotted the frontier during America’s westward expansion. They were established to keep the peace between settlers, railroad workers, and Native American tribes. The residence of the fort’s captain is now a very interesting B&B. Had we known of its existence, we would have made this one of our overnight stops.

Most towns had businesses that I’m sure the locals loyally patronized for there wasn’t much choice other than to drive hours to the next town over. With unique names such as Generous Gerry’s Fireworks and Magoo’s Tattoo’s, why wouldn’t you shop there!

Other towns had geographically and historically significant sites of interest. In Rugby, their claim to fame was that they were located at the geographical center of North America. In Minot, a replica of a wood stave church, common in medieval Norway and other parts of northwestern Europe, was erected in the town center in homage to the Scandinavian heritage of many who settled in this area.

In Montana, the open spaces and wide expanses of nothingness separated the sparsely populated towns. There was a certain beauty in the remoteness and starkness of our surroundings where views and observations otherwise mundane came into a focus in a more appreciative way.

Enormous farm combines, with their churning blades glinting in the sun, marched down the slopes of the gold-hued wheat fields side by side, like a battalion of tanks, kicking up dust from the chaff that floated over the road sometimes making visibility difficult. The fields were home to vast amounts of grasshoppers and other insects. They found refuge on the road, away from the harvest in the fields they once called home. Many met their demise as evidenced by their remains on our car’s grill and windshield. It reminded me of a saying comparing good days versus bad days: “Somedays you’re the windshield and other days you’re the bug.”

We confronted mile to mile and a half long trains on the tracks that paralleled the road, occasionally keeping pace with those that were heading in our direction. The loads were so large and so long that it sometimes took up to seven locomotives to haul the goods and cargo in the trailing boxcars.

Indian reservations were numerous. So too were their casinos. Some were fancy while others forlorn. An abandoned place of worship, with a name in a native language meaning “Pink Church”, sat high on a hill surrounded by an unkempt cemetery. Most of the plots had names typical of Native American culture and tradition, such as Sun Girl and George Long Knife.

Whimsical art and road side oddities were seen along the way. Some towns, like Glasgow, were proud of their middle of nowhere location and marketed themselves accordingly.

Glacier National Park

We overcame the winds and arrived at Glacier National Park via the Going to the Sun Road, an amazing road full of views and points of interest as it traverses and bisects the park. At Logan Pass, the parking area was packed with cars and people, even at the early morning hour when we arrived. Remote and isolated this was not.

We found a few parking spaces at a wide spot on the road a mile below. We walked along the shoulder back up to Logan Pass where the visitor’s center and various trailheads are located.

Signs suggest hikers carry bear spray due to the healthy population of grizzlies in the park. This was something I read about before the trip and dutifully purchased some from an online retailer. However, while almost every other hiker we saw carried an industrial-sized cannister and attached it to their backpack straps or belt loops, mine was of a very much smaller variety that fit inside the palm of my hand, more suitable to maybe deterring a determined Central Park mugger and not the menacing charge of an angry grizzly bear.

From the pass, we began our hike along the Highline Trail, a very popular, must-do trail if you are to day hike in this park. Along the first couple of miles, the trail parallels the Going to the Sun Road but does so along a precipitous ledge carved out of the sheer rock face of the wall that looms far above it.

At its narrowest, the Park Service has bolted into the rock wall a connecting series of chains which you hold onto while negotiating the narrow ledge. A slip here would lead to a gruesome death. Parts of your body would likely detach themselves from your pummeled torso as you bounced off of the rocks and crags protruding from the wall below. And then, in a final indignity, after you hit the road pavement hundreds of feet below, a passing car would run you over as a final good measure.

Commanding views of the Glacier Wall and other peaks and valleys came into focus as we made progress along the trail. Alarmingly though, what was left of the glaciers were small and growing smaller, receding rapidly up the valley. No wonder, for the temperatures have been in the mid-80s, way too high for this late summer/early fall date. The glaciers are simply no match for this kind of heat.

“What a shame,” a passing hiker commented looking at the same small glaciers we were looking at when we stopped for a trailside lunch at Haystack Butte Pass.

"I hear ya,” I replied back. “Perhaps they should consider renaming this park the ‘Not Too Many Glaciers Left National Park!’”

Numerous mule deer were seen both on and adjacent to the trial while on our way back to Logan Pass. We stopped to see several females and youngsters ahead of us. Nearby hikers called out saying that we should also look behind us. A male mule deer had apparently separated from the herd ahead of us and was looking to pass. Neither us nor he were alarmed at this confrontation. After a hesitating and cautious look, he scooted by with less than an arm’s length separating us and was soon back with his family.

More wildlife was seen when we later hiked up the Hidden Lake Trail. The first half of this trail was along a boardwalk that has been placed to deter people from wandering off and onto the adjacent fragile alpine tundra vegetation. The boardwalk eventually gave way to a gravel and rock path adjacent to various dwindling snow fields. On some of them, herds of up to a dozen or so bighorn sheep were laying down to keep cool from the unusual heat of our warming climate.

The next day, we embarked on a 14.5-mile round trip hike from the Jones Lake trailhead up to the Avalanche Creek trail which then led onwards to Avalanche Lake. Most of this hike was a long, contemplative walk through the deep and dark old growth cedar and hemlock forest. You could tell by the lack of wear on the trail’s tread that it is not walked by many others. But it should be since it is very quiet and serene.

In fact, we didn't see one other hiker for the many miles and two hours it took us before reaching the trail along Avalanche Creek where the popularity of the area grew due to many day hikers starting out from a nearby parking lot. The lake itself was disappointing. If you saw no other mountain lakes, you could say it was very pretty. But compared to the ones we have seen and hiked to, both here in Glacier and elsewhere throughout our travels, this one doesn't rate as well as the others.

Our final day in the park was spent at its northeastern corner. It is here that we received a whole new view and perspective of the park. Also, it is less visited and therefore less crowded. Our plan was to hike up to Iceberg Lake. However, due to heavy grizzly bear activity, the Park Service closed the trail to all users (even to those of us with both large and very tiny bear spray cannisters).

Instead, we hiked the south shore of Josephine Lake to Grinnell Lake about four miles distant. Portions of the trail veered off from the woods and followed the shoreline for a good distance. Views of the distant peaks, waterfalls, and permanent snowfields far above were spectacular and postcard-view worthy.

Eventually, the trail re-entered the bear infested forest for the remaining distance to Grinnell Lake. In fact, we saw a black bear browsing in the brush about fifty feet off of the trail.

We were greeted by a mini crowd of people once we arrived at the lake. A shuttle boat disgorged many of them who had motored in from a lodge in the area. Joining them were a newlywed couple (in tux and wedding dress) posing for their photographer with the mountains as their backdrop.

We walked down the shoreline a bit for some privacy to soak in the views of the amphitheater of mountains, snow, and waterfalls that nearly surrounded us. It was nice to sit and relax there after several days of hard hiking.

I noticed people moving along on the cliffside high up from the far shoreline. From our vantage point, they were tiny little dots of color among the grey walls of rock and stone. I used my binoculars to zoom in on them. Hikers were slowly climbing a trail that took them 2600 feet up to the perched glacier where one could touch the melt waters that fed the waterfall filling the lake we were now sitting next to.

I handed the binoculars to MK to take a look. “If instead of heading back to the car,’ I asked hopefully, “what would you think about continuing on and joining the others on that trail far above us?”

She was silent for a while as she scoped the far cliff-side. Handing the binoculars back to me, she said, "Fuck that."

And with that, our hiking in Glacier National Park had come to an end.

Back on U.S. Route 2

We pride ourselves on our efforts to travel on a shoestring. Doing so, we believe, allows for a more authentic travel experience. For example, we like to stay off of the tour buses and away from organized groups to make our own discoveries, shop in foreign grocery stores to make our own unique meals, and overnight in locally owned establishments to keep healthy the economy of the areas we are visiting. Doing all of this also allows us to stretch our dollars for use on yet more trips and journeys. However, traveling this way sometimes comes with unpleasant experiences and different kinds of costs.

Such was the case at our two-star Kalispell, Montana motel last night. The carpets were old, dirty, and threadbare. The scuffed cinder block walls (yes, cinder block) badly needed a paint job. The chairs in our room had numerous stains of dubious origins.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. We were woken up around midnight by another guest who had unlocked our door and entered our room. I bolted upright. “Who’s there!” I yelled. MK screamed. The unsuspecting lady who was mistakenly given a key to our room screamed as well. I don't know who was more frightened, her or us!! After checking to see if I soiled my shorts, we all went down the hallway to the front desk to sort out the mix-up and to make sure the lady was given a key to another room.

We tried to resume our much-needed sleep. But it came fitfully. Our mattress, which had to be one of the most uncomfortable ever, had a significant sag in the middle. It looked like the swayback of an old broken-down plow horse - and that is the way my back felt after sleeping on it!

We pulled away from the parking lot the next morning fuzzy and sleepy-eyed. “You sure know how to pick ‘em,” MK said wearily as she looked back at our jail cell-like motel, now receding in our rearview mirror.

We continued our Route 2 journey with a mid-morning stop in the mountain town of Libby, Montana. This small community was once ground zero of one of the worst man-made environmental disasters in American history.

It occurred over a period of many decades when the population was essentially poisoned by asbestos dust that had continually and consistently blown in from the area’s vermiculite mines. It has only been a couple of years since the EPA has declared the area “clean.” While hundreds have died, it is estimated that currently one out of every ten residents have an asbestos-related disease.

What does a town with such a dark history do to make it livable and more tourist friendly? “I know,” a chamber of commerce official had probably once said. “Let’s host an annual Chainsaw Carving Contest!!”

We happened to be passing through at the right time for men and women from all over the world had descended on this tiny village to compete against each other by carving and sculpting out of a raw, unfinished logs a statue or an image, usually of a wildlife figure or scene.

.JPG) |

| I love chainsaw-carved sculptures, don't you? |

.jpg) |

| You gotta get all the details just right. |

Most of the competitors travel the country, from contest to contest (apparently other chambers of commerce have had similar thoughts), and earn their living from potential prize money (the purse at this particular contest was a paltry $15,000) and by selling their work (we bought a small pumpkin carved from wood to add to our Halloween collection). "I am a wandering gypsy chainsaw artist,” one carver who called himself Thor, told us. “I don’t know if I make a living, but I do have a life.”

Down the road, we stopped at Kootenai Falls for a picnic lunch. Fly fishermen with gear in tow preceded us down a nearby trail. While they descended to water’s edge, we walked up and over the self-proclaimed Swinging Suspension Bridge (it lives up to its name, trust me!) that spans the river far above the rapids, falls, and cataracts.

From there, Route 2 entered into Idaho for a short journey across that state’s panhandle. At Bonner's Ferry, we reached the most northern part of our trip. There, we could see the nearby wildfires that were clearly visible on the slopes of the mountains that loomed over the town.

In Sandpoint, the downtown’s tourist-friendly shops catered to those out for an afternoon stroll. But not too friendly, mind you. After a daily dose of ungodly morning swill from our motels’ breakfast rooms, we were on an early afternoon hunt for a proper cuppa. But to our dismay, all of the coffee and pastry shops had already closed for the day.

We finished our last miles on Route 2, our old friend, while traveling through central Washington state. Scavenger birds, raven-like by their appearance, flittered and then flew off from their feast of a dead roadkill carcass as we approached them at high speeds.

Wheat field after wheat field stretched as far as the eye could see, much like what we experienced in west central Montana days earlier. Interestingly, the farmers in these here parts plow and plant their wheat right up to the edge of the road pavement. There are no road shoulders nor sizable rights of way in which there are fifty or so feet of ditches, grass, and then a fence before the plowed and planted field begins. Nope, not here. Wheat right up to the edge of pavement.

We left Route 2 for good when we detoured north toward Grand Coulee Dam, sometimes referred to as “the eighth wonder of the world,” The Columbia River waters it holds back are used to irrigate nearly 700,000 acres (do you like Washington State apples? Then thank Grand Coulee Dam). Its turbines generate enough electricity to power 2 million households throughout eight of our western states. It is said that the concrete used in its construction could create a 4-foot-wide sidewalk, 4-inches deep that would wrap around the world twice. It’s a marvel at what man can accomplish, isn’t it?

Man-made marvels changed to those nature made as we continued our remaining westward travels through the downstream Columbia River valley. Magnificent canyons and ravines (what they call “coulees” here) have created unique landforms and geologic areas of interest.

Much of what we drove through was created at the end of the last ice age when an ice dam formed in front of a massive glacier holding back its melt water. The dam gave way sending an enormous cascade of water miles wide and hundreds of feet deep speeding along at 65 miles per hour to create what we saw and traveled through today. My God! Can you imagine such a cataclysmic event?

.JPG) |

| The cataclysmic cascade of water rushed over the far cliffside creating a waterfall with a width and height much larger than today's Niagra Falls. |

Part Two – North to South

The route to our planned destination of Packwood, Washington and the eastern part of Mt. Rainier National Park was blocked due to wildfires, firefighting activities, and evacuations. This required the short notice change in plans I describe at the beginning of this trip report including a three-hour detour up and around the northern reaches of Mt. Rainier National Park and over to its western side.

Needing to stretch our legs and get some exercise, we first stopped at Snoqualmie Pass where we found a trailhead for a segment of the Pacific Crest Trail. This trail starts at the California/Mexico border to the south and runs 2,650 miles northerly to its terminus at the Washington/Canada border.

Needing to stretch our legs and get some exercise, we first stopped at Snoqualmie Pass where we found a trailhead for a segment of the Pacific Crest Trail. This trail starts at the California/Mexico border to the south and runs 2,650 miles northerly to its terminus at the Washington/Canada border.

Our walk was along a tiny, and I mean very tiny, five-mile portion of this epic trail. We chatted briefly with several thru-hikers, those that were hiking the entire route. One young man started his journey at the Mexico border back in early March. “It’s been quite the trip,” he told us, looking fit and trim. “And I’m on schedule. I’ll get to the Canada border by early October.”

Soon after we congratulated him on his accomplishment and bidding him continued good luck, we chatted with two other thru-hikers, both from England. “We’re loving our American adventure,” they said. “It’s been slow going, but we’re confident we’ll finish before the snows come.” There were some other day-hikers we briefly talked to, but no more thru-hikers. We were hoping to run into Reese Witherspoon but no such luck (for those that just got that joke, please raise your hands!).

We were fortunate to find a last minute and suitable alternative accommodation for the next several days when we later arrived in the town of Chehalis. This would serve as our base from which we would explore the western portions of the national park.

Mt. Rainier National Park

Mt. Rainier was brutish and muscular in an in-your-face kind of way. It just overpowered the scene in front of us. The views of grey rock and stone, covered here and there by enormous snowfields, dominated our views. Waterfalls and glaciers, heard cracking and groaning off in the far distance, descended from its flanks. Its heights, brilliant white with snow, came in and out of view as the clouds moved about.

We were on the Park’s signature trail, the six-mile Skyline Loop Trail, that took us from the Paradise lodge and parking area up and adjacent to this magnificent mountain. The entire trail was above the tree line and surrounded by alpine tundra which afforded unobstructed views.

This specific route and its side trips were recommended by Sandy, a very helpful and friendly volunteer ranger with the park service. His missing arm didn’t seem to deter him from regularly hiking the park’s trails and paths, some of which he was recommending we do in the coming days.

When on the trail later, a fellow volunteer was stopping all of us hikers, asking where we were from, what trails we planned on hiking, and then gave various tips and ideas on how to get the most out of our time here at Mt. Rainier.

We took him up on some of his ideas early in the morning on the following day when we headed up a three-mile path in the mist and fog to Snow Lake, a pretty little alpine lake sitting in a cloud enshrouded bowl surrounded by mountain sides and cliffs. We then took the three-mile loop around Reflection Lakes stuffing ourselves with trailside blueberries while waiting for the clouds to lift and for Rainier to show itself.

At least we thought they were blueberries for they certainly looked like them. They were growing wild everywhere along the trail. We were uncertain as to their edibility until we saw other hikers eating them by the fistful. That was enough to convince us that we too should indulge. And indulge we did. While they were delicious, they didn’t actually taste like a blueberry. But no one else was keeling over so we thought all was good.

Soon, another couple came around the bend in the trail and saw us munching away.

“Are these safe to eat?” they questioned as they began to cautiously nibble on the berries.

“We’ve seen many other hikers gorging on them so, yeah, we’re pretty sure,” I said between bites. “If not, we can discuss further when we meet you later at the E.R. when they pump our stomachs!”

They laughed nervously. “Maybe we can share a room!”

The delays caused by this fun and frivolity brought us to a late afternoon hour when the clearing clouds began to part themselves. Rainier took advantage and showed itself in all of its glory. The views were impressive both at Reflection Lakes and then later when we went on our last hike to view the Nisqually glacier, one of many Rainier glaciers with water falls and milky white water in braided, fast-moving rivers far below.

South Towards Oregon

We looked forward to visiting Mt. St. Helens to witness what the destruction of a devastating volcanic eruption of 40 plus years ago can do to the natural landscape. As we drove up the park road though, our mood darkened for the morning’s cloud deck had descended down to the levels where viewpoints were plentiful.

We watched a very informative twenty-minute movie at the Johnson's Observatory visitor’s center about the Mt. St. Helens 1980 eruption and the science and ecology learned from it. In dramatic fashion, after the movie ended, the screen and curtain behind it rose slowly to reveal an enormous picture window through which you could now see...wait for it....drumroll please.....NOTHING!

We were supposed to see the real thing: Mt. St. Helens in all its glory and grandeur. Instead, all we saw was a blank slate of grey clouds, fog, and spitting rains. We did however enjoy the various exhibits and first-hand accounts of those that survived the blast. They were miraculous and sobering all at the same time.

And hey, all was not for naught. We did buy a couple of nifty refrigerator magnets!

We arrived about 90 minutes later in the town of Longview. We met up with Dave and Paul, fellow travelers who we first met ten years ago. We were all sent to Ukraine as part of a U.S. State Department delegation to help teach democratic principles and local government best practices and procedures.

It was great seeing them again, catching up, and reminiscing about our past shared experiences a decade ago. We also lamented the on-going crisis there in a country we have collectively grown to love. We keep in touch with our friends back there and updated each other on how they and their families are doing the best they can with the unimaginably bad and very unnecessary situation of Russia’s making.

When our waiter took our group photo, he asked how we knew each other. Because we stumbled and hem and hawed as we tried to give him the background and details of our relationship he said, “Sounds weird. Were you CIA or something?”

After parting ways, our drive took us into Oregon, our 49th state. We smiled at each other when we crossed the Columbia River since as of now, we only have one state left to go (Hawaii), and we will have visited all 50 of our great United States.

We smiled again when at the gas station, we learned that there is no such thing as self-serve here. There are attendants that fill your tank for you. And, when I went inside to buy some goodies and gave the clerk a ten-dollar bill for a four-dollar charge, I got a full six dollars back, not a fiver and fistful of change. Seeing my puzzled look, the clerk said, “There’s no sales tax here in the State of Oregon.”

Highway 101 and the Oregon Coast

Earlier in the year, we were touring areas along the Atlantic coast. Here, six months later, we were now touring the sites along the Pacific coast following Highway 101 south through the State of Oregon. We have been most fortunate. I don’t think we have ever before been able to say we dipped our toes in two oceans all in the same calendar year.

Everywhere we went along Highway 101, we saw signs warning of tsunami hazard zones and where to drive (or run to) to find higher ground and safety. This got me to thinking: For how wonderful these areas in the west and northwest have been, it would make me pause to want to live here given the area’s history of giant waves, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, crippling drought, water shortages, flash floods, forest fires, evacuations, smokey air, avalanches, landslides, road closures….you name it. Makes living in the Midwest not sound so bad when all you have to do is endure a blizzard or two or perhaps dodge an occasional tornado.

Everywhere we went along Highway 101, we saw signs warning of tsunami hazard zones and where to drive (or run to) to find higher ground and safety. This got me to thinking: For how wonderful these areas in the west and northwest have been, it would make me pause to want to live here given the area’s history of giant waves, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, crippling drought, water shortages, flash floods, forest fires, evacuations, smokey air, avalanches, landslides, road closures….you name it. Makes living in the Midwest not sound so bad when all you have to do is endure a blizzard or two or perhaps dodge an occasional tornado.

But man! This sure is a scenic and beautiful part of the country!

At Cannon Beach, we walked the sandy beach and shoreline toward Haystack Rocks, a picture-worthy volcanic plug of basalt right off-shore that dominates the coastline view, now the home of gulls and puffins. We were there at low tide allowing us to walk right up to the rock. Volunteer naturalists walked amongst the gathered masses to describe to those of us willing to listen their explanation on the ecology and geology of the Rocks. They were also quick to warn us not to step onto the exposed barnacles and other sea creatures now clearly visible and exposed due to the low tide.

Later at Seaside, we walked the concrete boardwalk, or The Prom as the locals here call it, admiring the cottages, high rises, and tourist sites. Along the way, we noticed numerous wild blackberry shrubs full of ripe fruit. You know us. We couldn't let this pass (what is it with us and these wild, trail-side berries!). After stopping back at our hotel to retrieve a couple of quart-sized baggies, we returned to The Prom and filled them with 2 quarts of ripe, sweet, juicy, and delicious berries, all destined to be added to our breakfast cereal and yogurts in the days to come.

Numerous Lewis and Clark sites historical sites exist here and in areas near the mouth of the Columbia River. This area marked the final destination of their 1804 Voyage of Discovery journey in the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase to see if a water route existed from the east to the Pacific Ocean. There wasn't, of course, but they did reach the Pacific Ocean via various rivers and mountain passes and landed here near the mouth of the Columbia River. "Ocian (sic) in view! O! The joy!" Meriwether Lewis wrote in his journal.

.JPG) |

| This recreation of Fort Clatsop is where the Lewis and Clark expedition spent the winter of 1805/06 where rain fell for all but twelve days during their three-month stay. |

We stopped for a proper cuppa and a scone before sleepily and groggily making our way further south the next morning. You see, at 3 a.m. last night, the couple in the room above us began a marathon session of spirited and very energetic nocturnal activities. You could hear everything, and I mean EVERYTHING!!!, if you catch my drift. And the guy? We had to give him kudos since his endurance was most impressive. But after a while, enough was enough.

“Holy Jesus!” Mary Kay exclaimed after what seemed forever, squeezing the pillow around her ears. “Enough already! That poor woman!”

“Yeah, no kidding,” I said in false agreement. Truth be told, I harbored a secret. I had become envious of the guy and his staying power.

Down the road, we stopped at the Tillamook Creamery and walked along their viewing decks from which you could view the cheese making process. There were free samples, interesting self-guided tours, cheddar cheese this, and cheddar cheese that. Here, it was cheese galore!

Nearby began long stretches and grand vistas of the ocean, rocky cliffs, crashing waves, and distant and largely empty sand beaches. Whales breached the ocean’s surface spouting and exposing their massive tail fins right offshore. Historic harbor towns sheltered colorful fishing boats, bobbing in the gentle swells, waiting for their toil the following day. On the piers they were tied up to were lounging sea lions, their bellowing distinctive call heard from blocks away.

Near dusk, we slurped bowls of clam chowder at the world (at least in the part of the world) famous Mo's restaurant. In the dying light of the day, the silhouettes of historic lighthouses served to back-drop our casual stroll through oceanside neighborhoods and quaint commercial districts on the way back to our motel. Once there, we hit the feathers. Unlike last night, we hoped for a well-earned and, hopefully, full night of uninterrupted sleep.

We walked away from the shoreline and into the forest. The area's largest Sitka spruce tree was found on a poplar two-mile round-trip trail leading from the visitor's center. The 550-year-old tree is 225 foot tall and 15 feet thick. We were amazed at the thought that a seedling, sprouting from an otherwise unassuming pine cone, emerged from the soil before Christopher Columbus left on his first of many voyages to the Americas.

We later discovered solitude at Oregon Dunes Natural Area. After walking a mile or two through dunes and forest, we found ourselves on a remote, salt-sprayed beach. We likewise found ourselves to be the only ones there for miles in every direction. We lingered and enjoyed for such an experience is not something that happens often.

Crater Lake National Park